I'm off for vacation, but while I'm gone, try this exercise to imrpove your writing! Have fun!

When we watch a film, the characters are foisted upon us. The actors

are the physical manifestations of the characters, and their accents,

hair, faces, and clothes are no longer subject to our imagination.

When the actor matches the ideal of the character, the audience is by

and large content. But when the character does not match the actor,

then the audience is disappointed.

With books, the reader forms his or her own image, and if the

author's description doesn't match, the reader will be disappointed.

In order to avoid this, most authors describe their characters as

soon as they are introduced, allowing the reader to form an image.

Authors, while they are writing their stories, have very clear images

of their characters, and their description is an important part of

making the character come alive to the reader. If the reader cannot

imagine what the character looks or sounds like, they can have

difficulty identifying with the character. Identifying with a

character is vital – without that connection, a reader can feel

detached from the story.

Since everyone has a different way of imagining things, readers'

views of characters can vary greatly. An author can give a clear

picture of a character's sex, height, eye colour, hair and skin,

build, and clothing. However, when describing a character, the author

has to walk a narrow line between giving too little and too much

information.

Different genres of books deal with physical descriptions in vastly

different ways. It's almost a given that a book focusing on romance

will describe a character all throughout the book. It's a

manifestation of falling in love. When we fall in love, we think,

dream, fantasize about our love interest extensively. Therefore,

romance readers will readily identify with endless descriptions of

the physique and emotions of the characters. But readers need to

project their ideals upon the character. Too much description can

leave some readers feeling frustrated, especially as the book

progresses. Describing the characters over and over leaves very

little to the readers' imagination. The same with clothes – unless

the character is defined by the clothing or the clothing is important

to the story, it's best to be sparse with detail at risk of sounding

like a fashion magazine (admittedly, some readers like this).

In science fiction or horror stories, the characters are lavishly

described to the reader once at the beginning of the book in order to

set the tone of the story.

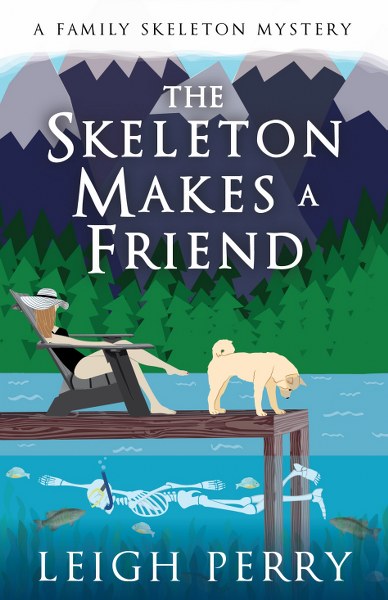

In murder mysteries, it's important to visualize the detective and

often the victim as well, so that the reader can identify with one or

the other.

In children's books, characters tend to be simply but well-described,

along with their traits of character. Pippi Longstocking comes to

mind, her description never varies: Pippi is red-haired, freckled,

unconventional and superhumanly strong – able to lift her horse

one-handed. She is playful and unpredictable. With that, the author

has given the reader all he or she needs to know to imagine the

character.

Most of all, description should be like a slightly blurred photo that

uses the reader's mind to add the details to bring it into focus.

Accent too plays a part – unless the dialogue is written in the

vernacular the reader will hear his or her own voice, with only

slight variations. For English readers, for example, Americans will

hear American accents, British the British accent, and so on. And

even if an American reader is reading a book set in London, the

American reader will not superimpose a British accent over the

dialogue unless prompted by spelling.

‘Ow, so lover-ly sittin' absa-bloomin'-lootly still,’ Eliza

Doolittle croons. The movie

'My Fair Lady' shows us how she looks and sounds – but in the book,

only creative spelling can show us 'ow, er, how,

she sounds.

Too much creative spelling can lose

a reader. Interest is held just as long as it's possible to read a

story and follow it without having to stop and try to figure out what

the author meant. Dialogue written in the vernacular has to be near

perfect – it's better for a beginning writer to try to portray a

subject's accent in small doses. However, a character can be

completely identified by speech patterns. If I write; ‘Use

the accent sparingly, you must’,

a certain Yoda springs to mind!

Punctuation is another thing an

author can use to show what a character is feeling. Exclamation

marks, dashes, italics, cut off sentences, etc., are all part of the

manifestation of a character's personality. Punctuation in a dialogue

can show a reader what a character is feeling better than just

telling the reader what the character feels. Use exclamation points

as sparingly as possible – too many, and the reader feels yelled

at!

Here is an exercise for you; write a

short (2 or 3 lines at the most) paragraph introducing and describing

the same character for different genres: romance, science fiction, YA

(or children's book), mystery. You can even add a line of dialogue if

it helps describe the character as well.

Have fun!